Programme approach

The OER Programme took a broad and inclusive approach to the definition of open educational resources. The call Briefing Paper on Open Educational Resources2 for the Phase One Pilot Programme described learning resources and open educational resources as follows:

What are learning resources?

Whilst purely informational content has a significant role in learning and teaching, it is helpful to consider learning resources by their levels of granularity and to focus on the degree to which information content is embedded within a learning activity:

- Digital assets – normally a single file (e.g. an image, video or audio clip), sometimes called a ‘raw media asset’;

- Information objects – a structured aggregation of digital assets, designed purely to present information;

- Learning objects – an aggregation of one or more digital assets which represents an educationally meaningful stand along unit;

- Learning activities – tasks involving interactions with information to attain a specific learning outcome;

- Learning design – structured sequences of information and activities to promote learning.

What are open learning resources?

The term Open Educational Resources (OER) was first introduced at a conference hosted by UNESCO in 2000 and was promoted in the context of providing free access to educational resources on a global scale. There is no authoritatively accredited definition for the term OER at present; the most frequently used definition is, “digitised materials offered freely and openly for educators, students and self-learners to use and reuse for teaching, learning and research”.3

The UK OER Programme Call FAQ4 eludicated this definition further:

Open educational resources can be defined as ‘teaching, learning and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use or re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, material or techniques used to support access to knowledge’

Issues

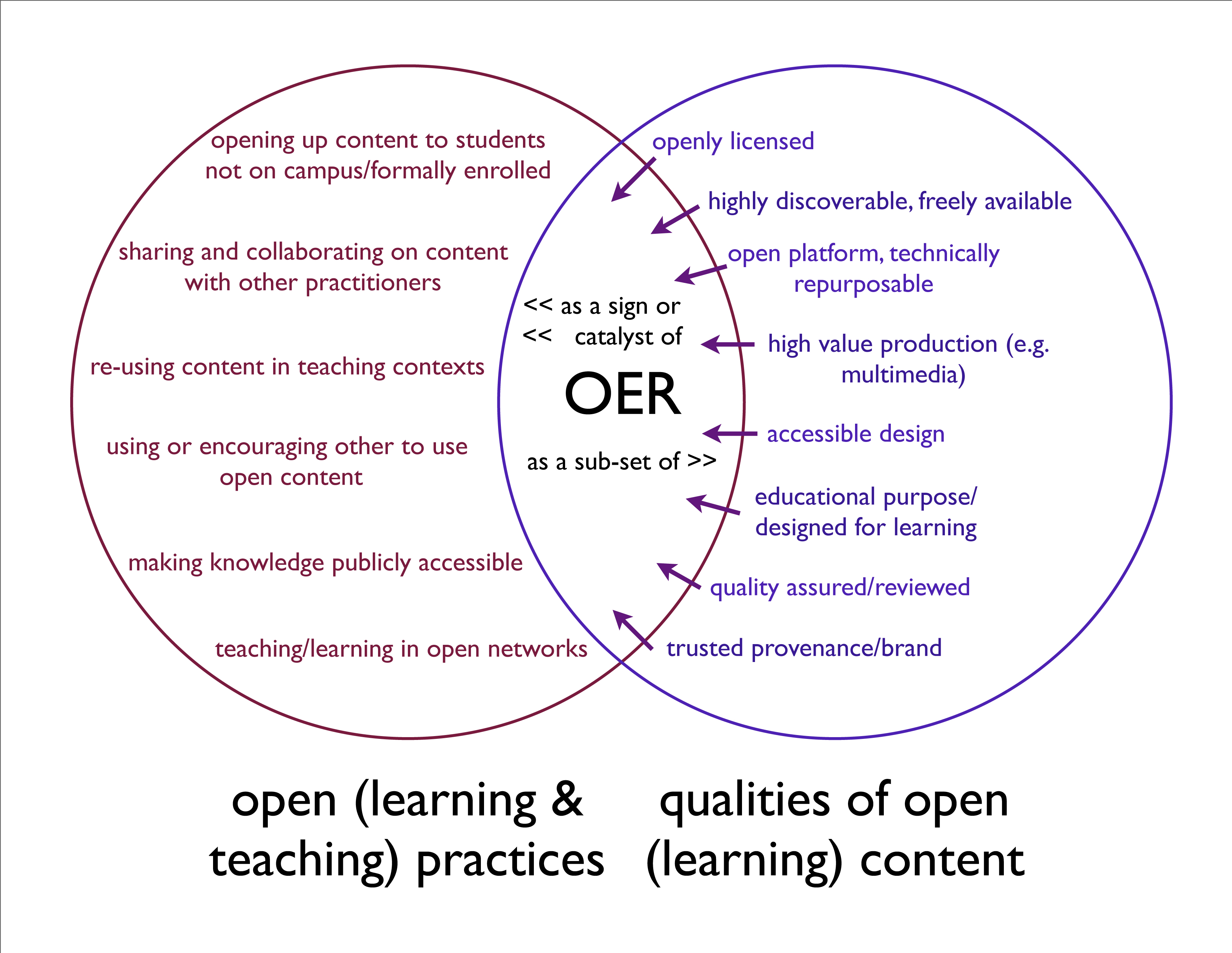

Open content and open practice

OER re-use and repurposing

In a blog post on “Rethinking the O in OER”8, Programme Manager Amber Thomas challenged readers to consider the characteristics of open educational resources.

Consider whether the following can be regarded as open educational resources:

- A PDF.

- A MS Powerpoint .ppt file.

- An html page with no licence information.

- An IMS content package.

- A PDF licensed as CC BY SA.

- A jpeg image.

- A website licensed as CC BY NC.

- An iTunesU podcast.

- An OpenOffice document licensed as (c) all rights reserved.

Open is multi-dimensional

Clearly there is a technical dimension to openness as well as a legal one.

Technical questions to consider in relation to openness include:

- What software is required to access a resource?

- Do users have to log in?

- Do users have to pay?

- What software is required to edit a resource?

- What skills are required to edit a resource?

Returning to the list of potential open educational resources above,

- An MS Powerpoint .ppt file (2), is proprietary but ubiquitous, easy to view, easy to edit.

- An IMS content package (4), is non-proprietary but specialist. Users need to have the right software, which may not be commonly available. However with the right software and specialist knowledge the resource is easy to view and edit.

- An iTunesU podcast (8), is proprietary but common. Users must pay for a specific platform to access the content. The content is then easy to play but can not be edited.

Some formats place implicit constraints on re-use. PDFs for example are only available on a no derivatives, share-alike basis; they are intended to be read but not edited.

We need to understand more about how OERs are used in practice, particularly with regards to the importance of editability.

Is “use” good enough?

Learning technology is historically bound up with the search for the holy grail of repurposing: academic finds a resource, downloads it, edits it and uses it with their learners. This has been the vision for well over a decade. How often does this happen? How do we know? Studies such as “Good Intentions: improving the evidence base in support of sharing”15 suggest there is plenty of literature about reuse and repurposing but perhaps less compelling evidence of it actually happening.

However many academics use online content to reflect on and inform their teaching and thinking on a subject. Similarly many academics use CC images from flickr simply as illustrations for slide presentations. This may be just “use”, rather than “repurposing” but it is still of considerable value to individual users.

Furthermore it is perfectly valid to reuse resources without repurposing them. Academics are never chastised for failing to write in the margins of a novel, or for not editing a film down to its highlights. The expectation for many teaching and learning resources is that they will be used complete and in their entirety. Furthermore it has become increasingly easy to share resources by embedding, leading some commentators to suggest that, in terms of reusability, <embed> changes everything. If this is the case, then what is wrong with simply reusing an OER as is? Is repurposing an OER really more educationally valid that simply reusing it?

Users do need to be able to cite or quote a resource to use it effectively in an educational context. To cite it they need the url and attribution information, which is another reason for clear licensing content. However it is questionable whether a robust citation model exists for teaching and learning resources of any kind. Provenance is important to evaluating the relevance of the resource, but are citations used to situate resources in the wider context?

Another question to consider is whether and how often a learner is likely to edit a resource. How common is this use case? What if the content that has most chance of being read, played, repeated, absorbed, is the content that is suitable for the learner’s personal mobile device? And what if that device is proprietary? Is there a disconnect between the move towards open content and standards and the reality of ubiquitous cheap computing?

What we do and don’t know about use

It was hoped that the Programmes would start to answer some of the above questions while at the same time uncovering information about the reuse and repurposing of the OERs produced. However, as described in the Tracking OERs chapter, this data is very hard to capture.

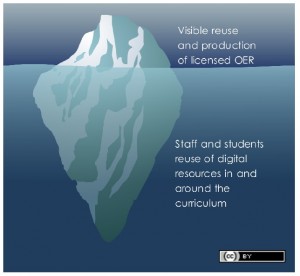

The OER Impact Study Research Report9 by the University of Oxford, commissioned by the UK OER Programme, used an iceberg analogy to illustrate visible and invisible reuse.

White, Manton et al (2011) Visible and invisible reuse of digital resources 17

David Wiley’s “OER, Toothbrushes, and Value”16, blog post is another frequently cited example of this conundrum. The fact that Wiley’s post proved to be so divisive amongst the OER community shows that it hit a nerve (excuse the pun).

Following the iceberg analogy, there is general consensus amongst those involved in UK OER Programmes that there is above waterline use and below the waterline use. So reuse of web-based resources does happen, all the time, but it is usually private, mostly invisible to the providers and often not strictly legal.

In terms of the data available, the interpretation has to be either that re-use is not happening at scale, or that it is not happening in ways that can be captured within the current digital infrastructure. As the chapter on Paradata illustrates, new and innovative approaches are being developed in an attempt to surface and record resource reuse. However the conclusion from the UK OER Programmes must be that there is currently insufficient rich data available to inform the decisions of service providers.

Learners and OER

Much of the analysis undertaken around the UK OER Programmes focused on educators’ use of open educational resources. However part of the way through the Programme it became apparent that there was no systematic data being collected about learners attitudes towards the use of OERs, either for self-directed learning online, or more formal learning, mediated by educators.

The “Learners Use of Online Educational Learning Resources”10 report was a systematic literature review commissioned by the UK OER Programme to fill this gap.

The review found a lack of reliable data on learners use of OERs, even though the scope was widened to look for learners use of online resources more generally. Despite many of the OER projects engaging with learners, the review reported that:

“The JISC/HEA OER Programme has so far produced relatively little data on learner use (some partial exceptions are noted). This is to a lesser extent true for all OER literature – but the non-OER literature is much richer.”

The review clearly illustrated the state of the evidence base about learners use of, and attitudes towards, “OER”. Specific points salient to digital infrastructures included:

- Learners’ rationale for searching for online resources: The OER literature is dominated by the large open university and MIT studies. It is debatable how applicable these are to the generality of UK universities and their students. The non-OER literature typically addresses this issue from the standpoint of assessment-driven student behaviour. There is clear room for studies looking at the middle ground.

- Types of online resources being sought: JISC/HEA OER projects encompassed a wide range of formats and noted the student preference for audio over video confirmed by non-OER work. The project work still seems dominated by supply-side aspects. Non-OER work confirms the commonly held view that today’s learners utilise numerous types of media. They hint at the primacy of Wikipedia and journal material, but quantitative information is scarce.

- Complexity/granularity of resources being sought: OER studies tended to confirm the tension between specificity and potential for reuse (seen since the early days of RLOs). Also, students want narrative structure in, or above, the resources they use. The non-OER literature seems to focus more on students typically seeking a single item per search and hints at the assessment-driven paradigm again – or filling in gaps in an existing narrative, not creating their own. It is tempting to draw the conclusion that the two types of study are in fact addressing two different student populations. Again there is clear room for studies looking at the middle ground.

- How resources found are used: This leads on from the last point. Interestingly the two types of study have more in common here, with the exception of the set of OpenLearn students ‘overloading’ their use of resources with expectations about social networking and assessment. Possibly the topic needs to be refined to distinguish between ‘How resources found are used’ and ‘How services providing resources (and other things) are used’. Depending on how fast portfolios based on the Higher Education Achievement Report come into common use, some convergence is possible.

- Enablers and barriers to use of online resources: It remains true across the wider research that most of the barriers to the use of OER are the same as/or a consequence of more generic barriers to accessing and using technologies for learning. However, the issues of designing learning for the unknown user and the tensions between granularity and the need for scaffolding permeate much of the research. Esslemont (2007) puts it pithily: “There are several interlinked issues related to completeness of content, granularity, copyright, offline access, use, etc., that sometimes limit the effectiveness of material provided. Therefore in order to support the learner we need to understand and support … the learner’s limitations in terms of content selection, access, use and management of their personal knowledge silos on their desktop.” Other barriers include: young peoples’ reliance on search engines to ‘view rather than read’ and ‘readily sacrifice content for convenience’. Students would like guidance but can be reluctant to work with librarians. Publishers’ restrictions on materials can put off students when they cannot access results they find by searching.

- How learners retain access to the resources: In this area there seems to be just one key study – Lim11 on Wikipedia; who reports that slightly more than half of the respondents accessed Wikipedia through a search engine, while nearly half accessed it via their own bookmarks. Some students still like paper and will print out longer texts if given the chance. A few use more sophisticated tools.

- Provenance information and copyright status of resources being used: Students have inconsistent attitudes to provenance. The experience of the OUNL OpenER researchers is overwhelmingly that students expect the courses to be of a suitably academic level and that the university is the guarantor of quality. Elsewhere many students seem content to take on trust the validity of resources found on the web. Students tend to use Wikipedia for rapid fact-checking and background information and have generally had good experiences of it as a resource. However, their perceptions of its ‘information quality’ did not reflect this: it appears that the uneasiness associated with the anonymous authorships of Wikipedia has led to non-expert users’ underestimation of its reliability. Students are not generally sophisticated in their understanding of things like peer review or currency: they are weak at determining the quality of the information that they find on a website, and may in fact judge the validity of a website based on how elaborate it looks. In a study analysing young adults’ credibility assessment of Wikipedia, a few lacked even such basic knowledge as the fact that anyone can edit the site.

- Beyond these topics, some other issues cropped up:

- Students discover online resources in multiple ways: e.g. in the Open Nottingham project survey, 35% of respondents said they had previously used OER and, of these, 67% had found resources through browsing, 56% had used a search engine, 33% had been told of the resources by lecturers and 6% were from peer recommendations.

- Numerous studies identify university libraries as a critical conduit to digital resources.

- Learners are found to be predictable in their choice of digital resources, and to rely on tools that have worked for them before.

- Almost everyone starts with Google; and wants their digital library to be more like it.

Libre vs gratis OER

Finally, one of the key criteria for OER is free access. There is some commonality here with open source software and open access to scholarly works developments and also to the free culture movement in arts and cultural heritage sectors around the world. Content that is freely available online, but which is not CC licensed and can not be edited, falls outwith the stricter definitions of OER. This echoes debates in the open source software world about gratis vs libre.12 How important is access to editable source code, and how important is free-at-the-point-of-use? While all the content released by the OER Programmes was CC licensed and therefore may be regarded as both libre and gratis, in reality, it may not always be easy to re-edit some of the OERs produced.

- HEFCE/Academy/JISC Open Educational Resources Programme: Call for Projects, (2008), http://www.jisc.ac.uk/fundingopportunities/funding_calls/2008/12/grant1408.aspx ^

- JISC, (2008), Briefing Paper on Open Educational Resources, http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/funding/2008/12/oerbriefingv4.doc ^

- OECD, (2007), Giving Knowledge for Free: the Emergence of Open Educational Resources, http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/38851849.pdf ^

- JISC, (2008), Open Educational Resources (OER) frequently asked questions, http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/funding/2008/12/oerfaq.doc ^

- Beetham, H., (2012), What are ‘open educational practices’?, https://oersynth.pbworks.com/w/page/51685003/OpenPracticesWhat ^

- JISC, (2011), Strand A: Digitisation & open educational resources (OER), http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/digitisation/content2011_2013/Strand%20A.aspx ^

- McGill, L., (2010), OER Synthesis and Evaluation Project, https://oersynth.pbworks.com/w/page/29595671/OER%20Synthesis%20and%20Evaluation%20 ^

- Thomas, A., (2010), Rethinking the O in OER, http://infteam.jiscinvolve.org/wp/2010/12/10/rethinking-the-o-in-oer/ ^

- Masterman, L. and Wilde, J., (2011), OER Impact Study: Research Report, http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/elearning/oer/JISCOERImpactStudyResearchReportv1-0.pdf ^

- Bacsich, P., Phillips, B, Bristow, S.F., (2011), Learner Use of Online Educational Resources for Learning (LUOERL) – Final report, http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/elearning/oer2/LearnerVoice.aspx ^

- Lim, S., (2009), How and Why Do College Students Use Wikipedia? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(11), http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1656292 ^

- Gratis versus libre, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gratis_versus_libre ^

- Korn, N., (2010), How Open are So-Called ‘Open’ Licences?, in Overview Of the ‘Openness’ of Licences Selected by JISC Projects to Provide Access to Materials, Tools and Media, http://sca.jiscinvolve.org/wp/files/2010/08/SCA_HowOpenIsOpen_v1-03.pdf ^

- Web2Rights OER Support Project, Risk Management Calculator, http://www.web2rights.com/OERIPRSupport/risk-management-calculator/ ^

- McGill,L., Currier, S., Duncan, C. and Douglas, P., (2008), Good intentions: improving the evidence base in support of sharing learning materials, http://ie-repository.jisc.ac.uk/265/1/goodintentionspublic.pdf ^

- http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/1780 ^

- http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/1780 ^

- http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/elearning/oer2/oerimpact.aspx ^